Translator: Derek Gromadzki | Author: Gozo Yoshimasu | Work: Alice, Iris, Red Horse: Selected Poems of Gozo Yoshimasu: A Book in and on Translation | Original language: Japanese | Genre: Poetry

When I began working with Forrest Gander on his selection of Gozo Yoshimasu’s poetry, Alice, Iris, Red Horse, I confronted what I thought were two very different, even conflicting, translator’s tasks. First, I was asked to edit and reformat the translators’ notes for each poem included in the manuscript. Yoshimasu had requested that the notes drafted to accompany his poems not appear as the traditional notational apologia for texts and their translations. The single guideline he spooled out was that they should better approximate the modality of the poems they glossed. Second, and a bit later into the project, I received an invitation to collaborate with the Japanese translator Sayuri Okamoto in co-translating a long excerpt from Yoshimasu’s Naked Memos, which would be incorporated into the selection Forrest had made.

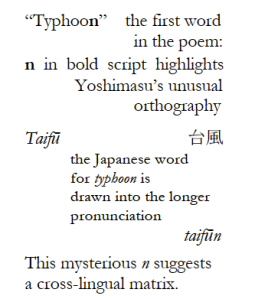

As I wondered how to impart poetry to the notes without irreparably eschewing their function as notes, it occurred to me that Yoshimasu’s Japanese tategaki texts had been wrenched out of verticality and subjected to horizontal conformity in translation. In somewhat playful recompense, I decided to align the text of the notes in vertical columns. Still, the change was not a sufficient match for the spatial, the typographic variability of the poems. Then, looking at the columnar notes alongside the poems, I realized that I could start breaking them apart and moving them around as if they were a construction material to be salvaged and repurposed according to Yoshimasu’s singular blueprint for the poetic page. A striking feature of his poetry is what it does physically, materially, before or as it succumbs to reading for content. Hints of strange visual and, out of these, cognitive-acoustic patterns emerge then slip away. Moving forward on the assertion of space as the fundamental sensory datum and that from the inference of matter in it, its observation and grammatization, duration follows, I tried to achieve a level of spatial heterogeneity in the notes tantamount to what existed in the poems. Doing so, I thought, would incite a reader to more actively participate in the otherwise unnoticed mechanisms of duration – to puzzle out, to read with a more individual or diachronic time signature unique to her or his experience with Yoshimasu’s writing than the homogeneity of standard notes would have allowed.

This decision of course proved subversive to traditional notions of translation. But more interestingly it also subverted, in tandem with the text and in however minute a measure, the growing, globally socialized construction of time as one homogeneous present wherein the tripartite temporal paradigm of past, present, and future, dissolves. The more closely we hew to vectors of technicization bent on turning time into an infinitesimal interval, the more rapidly our individual procedures for constructing duration recede from us. This recession runs apace with the technological apparatus enabling global sociability, which remove matter – so necessary for constructing duration – from physical space and replace it with immediate, virtual omnipresence.

Meanwhile the devilish irony looming over this whole enterprise is that my collaboration with Sayuri depended on devices conducive to just this distortion. Our communication often skipped instantaneously back and fourth between different parts of the United States, Europe, and Japan, but we did not once meet in person while working on the translation; our schedules simply prevented all such encounters. Our means of interaction could scarcely have been at greater odds with the theoretical conventions I had devised to solve the problem of the notes. Without the support of integrated, digital communication networks, our work would likely have foundered.

Do the circumstances under which Sayuri and I translated together undermine the credibility of how I spatially translated the notes and why I chose to translate them the way I did? I do not think so; not quite. Sayuri and I communicated via e-mail daily, sometimes once or twice hourly within the span of a day, at which point the pace of our exchanges grew so rapid that we both found it more productive to withdraw from the immediate, integrated present. Why? What became apparent was our desire for actual rather than virtual space and for presence within that space, diachronically cordoned off outside of global synchrony, where we could feel our own time pass at the pace of gesture observed, of spatially and materially present conversation as we traded ideas and suggestions. The Internet was and continues to be a means of overdetermining the present, and also of mitigating distance, but not of obliterating it. For us it was always a second choice even if, practically, the only choice. And inasmuch as it continues to neglect certain necessities of human interaction, it turns our attention, through their absence, to a reconsideration of just what those necessities may be. If I were to begin compiling a list, near its top would be, as it were, a time apart.

Derek Gromadzki received his MFA in poetry from the Literary Arts Program at Brown University, where he held the Peter Kaplan Memorial Fellowship, and is currently a Presidential Graduate Fellow in Comparative Literature at the University of Iowa. His poems have appeared in a variety of publications, including American Letters & Commentary, Colorado Review, Drunken Boat, The Journal, the PEN Poetry Series, Seneca Review, Wave Composition, and Web Conjunctions.